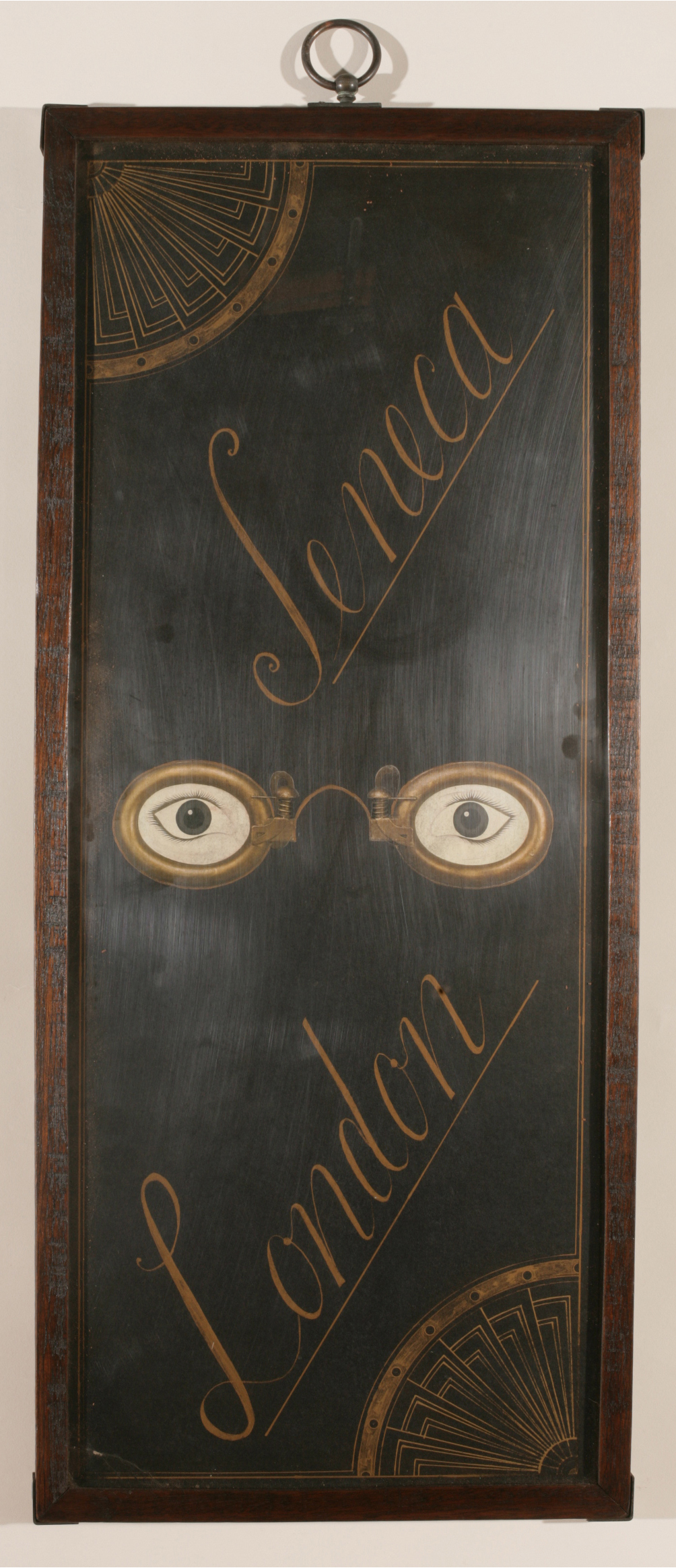

The Seneca Collection

2010 – The Seneca Collection – Rose Issa Projects, London.

“In the diversity of the world’s languages we find facts about ancient human history, the path of languages through time, and deep knowledge of the planet…..languages and their speakers offer a scientific bonanza to anyone trying to understand human evolution, behaviour and cognition”.

Christine Kenneally 2010

In 2000, the British Council invited me to propose an art installation to exhibit as part of a cultural exchange with Iran. I began by looking at Persian art history and noticed how it had been influenced by other cultures from both east and west.

Back in the early 60s I had read and admired the book, Notes from a Bottle found on the Beach at Carmel by Evan S. Connell. From this collection of ominous anecdotes I always remembered the following:

“The first Ch’in Divine August One learned, to his satisfaction and dismay, that he had conquered every civilized land, for he believed that beyond the borders of his empire nothing existed but howling winds and barren waste. At this same time Alexander had overrun the Western world. So it was that two men not knowing of each others’ existence shared a common delusion.”

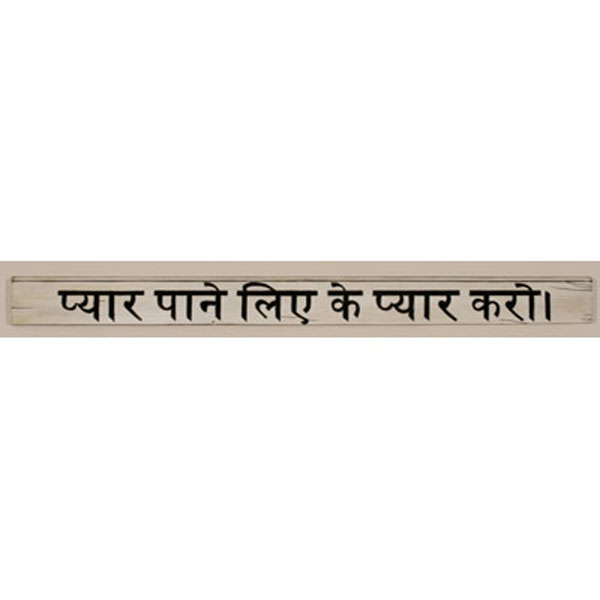

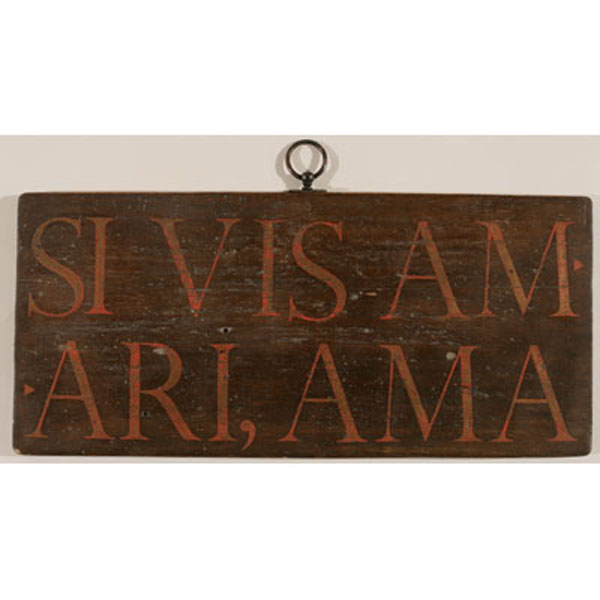

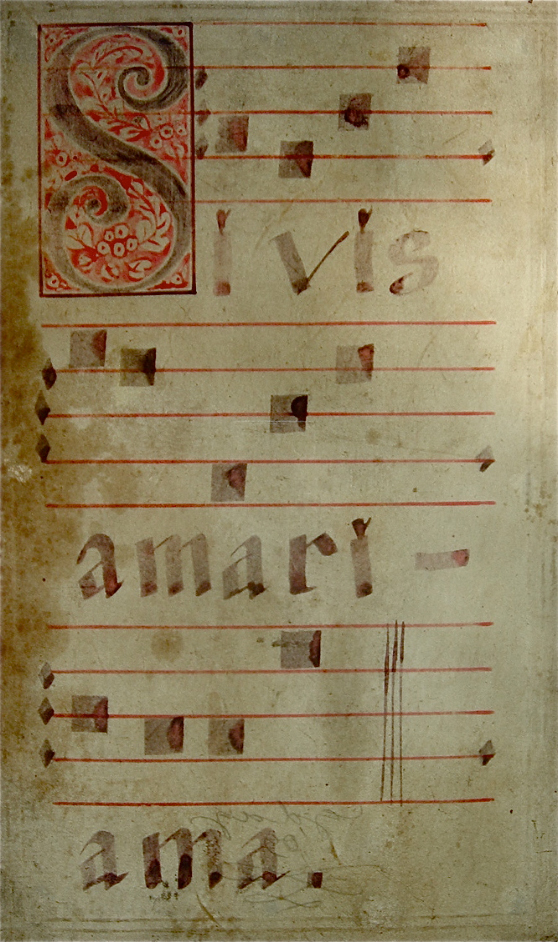

To illustrate something along those lines I used a proverb I had read in a 19th-century book, Beautiful Thoughts by Latin Authors: “Si vis amari, ama” – “If you wish to be loved, love” – a universal concept attributed to the Roman philosopher, statesman and dramatist Seneca (c. 4BC-AD65).

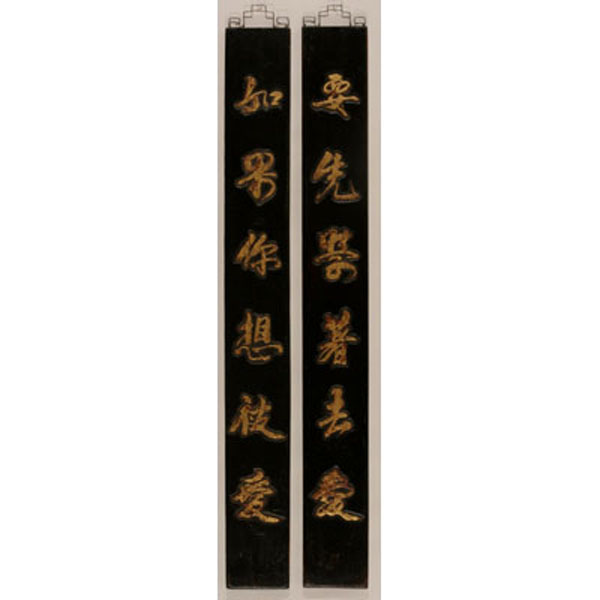

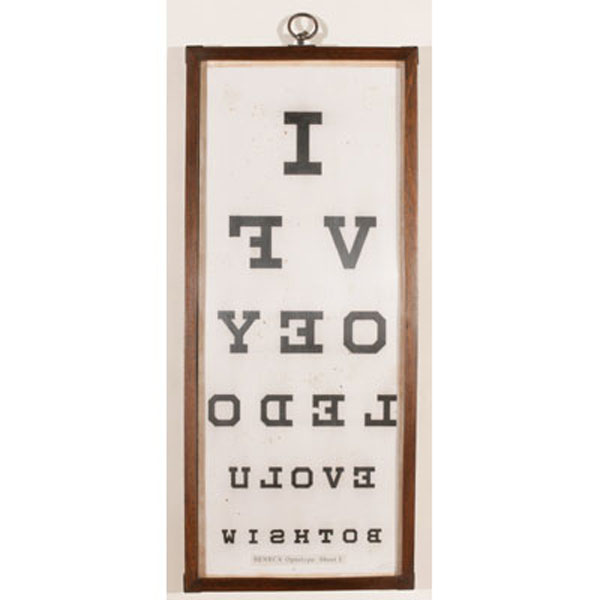

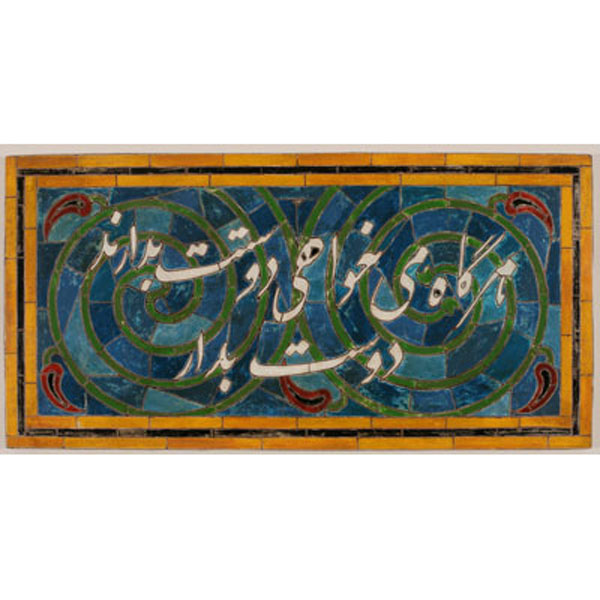

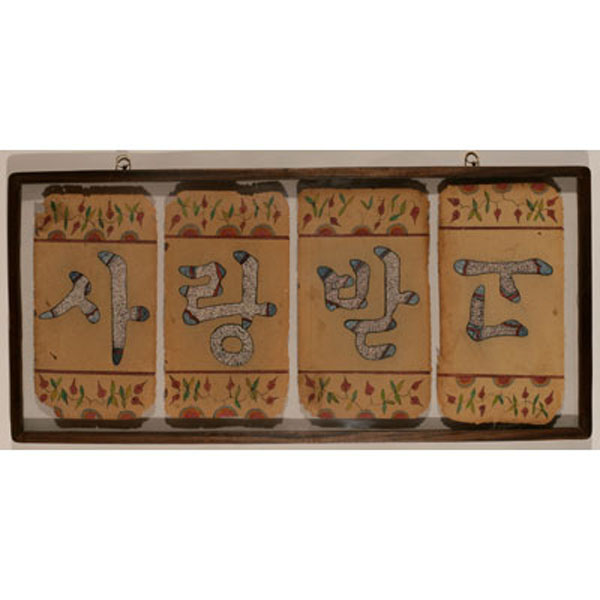

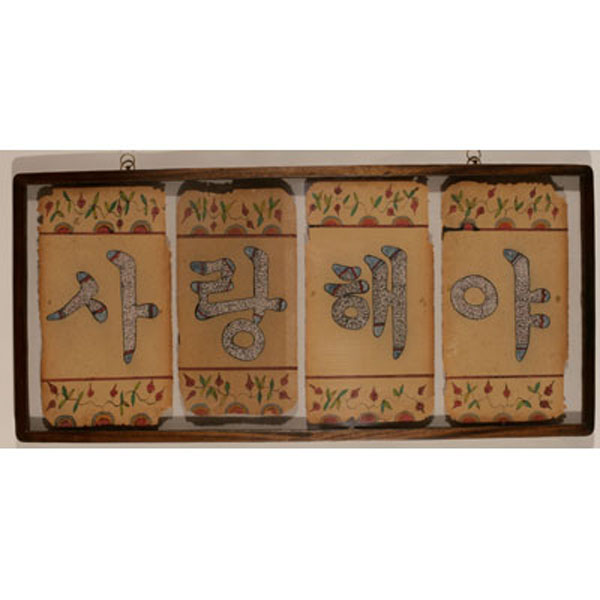

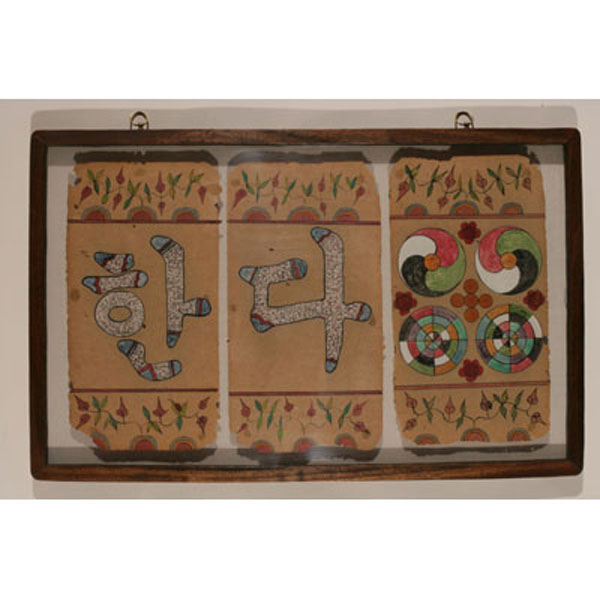

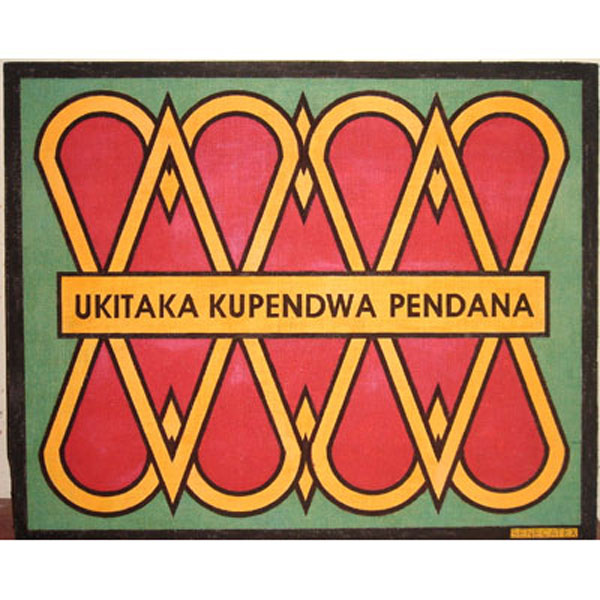

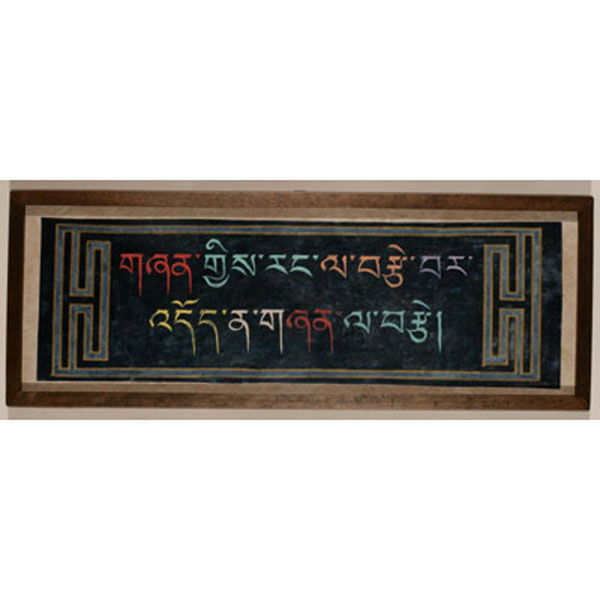

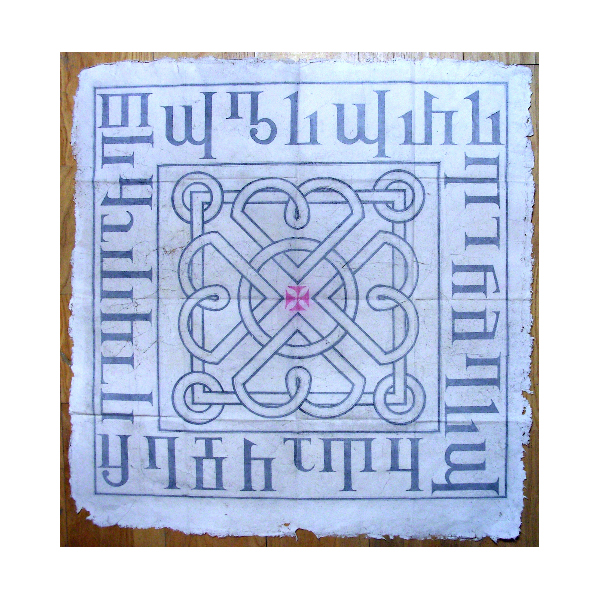

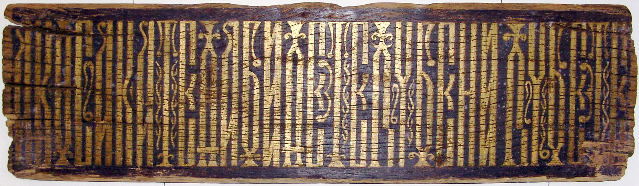

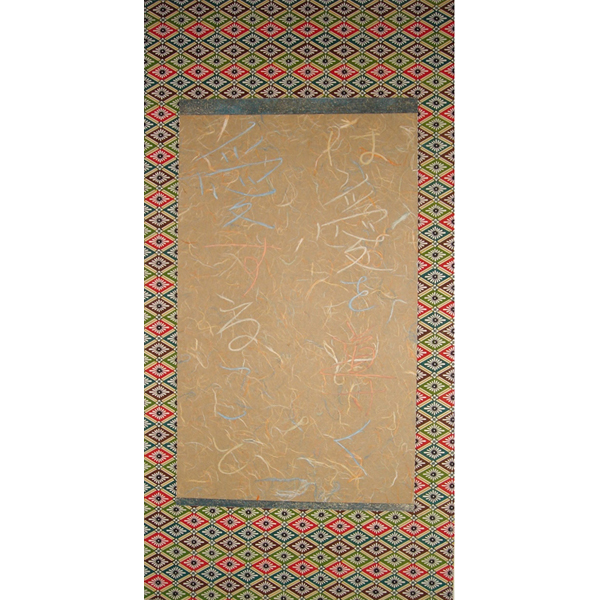

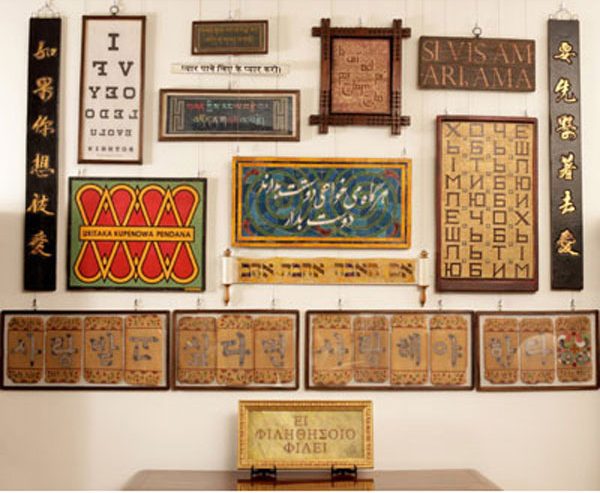

I had the original Latin text translated into Farsi, the language of Iran; then into Chinese for the East; and Greek for the West, and set about making three artworks to show together, with Iran in the middle. The Chinese was carved and gilded onto two planks of wood; the Farsi was a mosaic of simulated tiles; and the Greek carved into marble, to make the works appear as if they were from the culture of each script. This sampling was justified in my mind by the sincerity of the depicted message.

Other literary influences were the short stories by the Argentinean writer J.L. Borges, and the fantastic yet completely believable objects he depicted in The Aleph and The Library of Babel, for example. My three texts said the same thing but were unconnected until I came along and “collected” them, presenting them to the public in the same way as different objects of the same function are displayed in ethnographic museums. Another influence was Marcel Duchamp and his fascination for word play, which was inspired by the French writer Raymond Roussel’s fastidiously eccentric fiction in New Impressions of Africa and Locus Solus. According to Taiwanese art historian Tosi Lee in his essay, Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, Duchamp was a crypto-Buddhist with constant hidden esoteric Buddhist references throughout his work. As the message in Seneca’s proverb and my work presented here reflects the basic Buddhist message, Duchamp makes even more sense. Also, Duchamp said, “The minute you talk, you spoil the whole game.”

With help from others (my contribution I call Conception and Patination – the Alpha and Omega of the making of an art object), the original triptych was ready in early 2001, and the show in Teheran was scheduled for early October. Then came 9/11, the British Council panicked and cancelled everything, claiming that they could not insure the project and people involved. My work was now without its context, leaving it lacking and invalidated. It hung around the studio, sulking and demanding attention. After a while the answer became obvious – fill in the gaps between the languages, unite the world and create a collection of the same thing, thus demonstrating the truth of Seneca’s proverb. By exhibiting the works together, the message becomes universal.

Graham Day 2009