The Conference of Birds

2002 – The Conference of the Birds – Mary Ogilvie Gallery, Oxford.

Hilary 2002 – The Mary Ogilvie Gallery, St Anne’s Oxford.

The printed image fascinates Day who was born in central London in 1946. As student he worked with John Furnival and the Concrete poets at Bath Academy of Art going on to do postgraduate studies at the Slade School of Fine Art at UCL. He has lectured on iine art at various universities since 1973.

During 2001 solo exhibitions of his work were shown in the city library in Los Angeles, U.S.A., The Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran, Iran and Galerie Janine Rubeiz in Beirut, Lebanon.

His work can be found in the public collections of the British Library, British Museum and The Victoria & Albert museums in London; the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris; The Museum of Modern Art in New York and numerous private collections.

The Manteqat-Tair, known as The Conference or Parliament of Birds, is a mathnavi, i.e. a poem in rhyming couplets composed towards the end of the twelfth century by Farid ud – Din Attar, the celebrated Persian poet from Nishapur in north – east Iran.

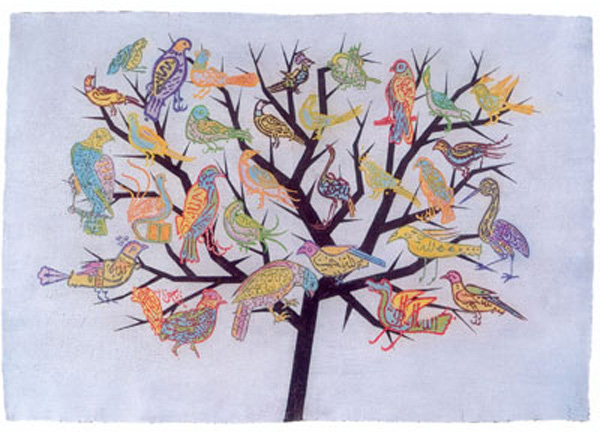

It is an animal fable that involves the birds of the world in their search for their king, the Simorgh. The birds, who represent a range of human archetypes such as the timid finch and the coy duck, elect the hoopoe – because of its knowledge of the world gained whilst acting as courier between King Solomon and Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba – to lead them to the object of their desire. Each bird expresses its reservations and apprehensions about the journey ahead; each in turn is placated by the hoopoe. The journey takes them over seven valleys that chart the progress of the aspirant. Only thirty birds survive the arduous voyage and these thirty (si in Farsi) birds (morgh) finally come face to face with the Simorgh. This pun is the crux of the tale: they are confronted by themselves.

Sources for Attar’s story can be found in an earlier poem in the Divan of Sana’i, in which the different cries of the birds are interpreted as the birds’ way of calling on or praising God. A second source may well have been the Kalila wa Dimna; this extraordinarily popular work, also called the Fables of Bidpai. orginated in India and was translated into many languages. Another work which probably influenced Attar is the Arabic treatise The Bird by Avicenna. This is the first person narrative of a bird ( clearly representing the human soul ) who is freed from a cage by other birds, and then flies off with his new companions on a journey to the ‘Great King1 Annemarie Schimmel writing about Jalalodin Rumi, describes bird imagery before Attar: “The Koran has attested that birds have their special language which is understood by Solomon (sura 27/16) … take four birds and slaughter them” (sura 2/262) these birds are explained as the duck ‘greed’, the peacock’ eminence’, the crow ‘worldly desire’ and the rooster ‘lust’. 2. The imagery in Graharn Day’s monoprints is derived from popular talismans found in the Middle East and India. Zoomorphic calligraphy is not exclusively Persian, Arabic or Turkish; there are numerous Greek, Hebrew and Chinese examples.

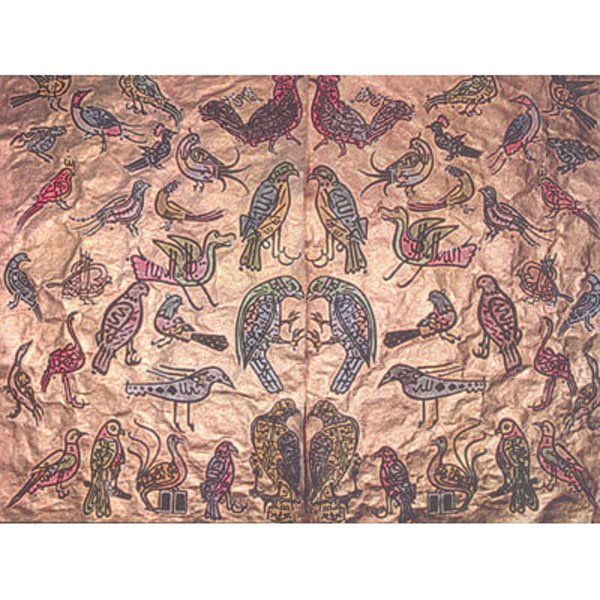

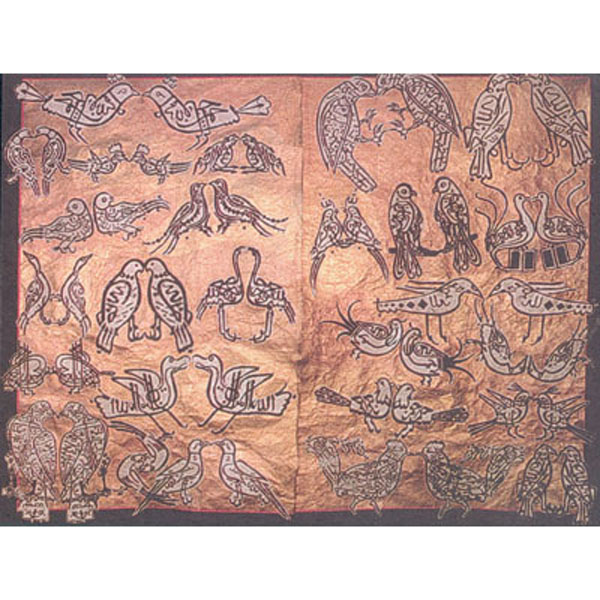

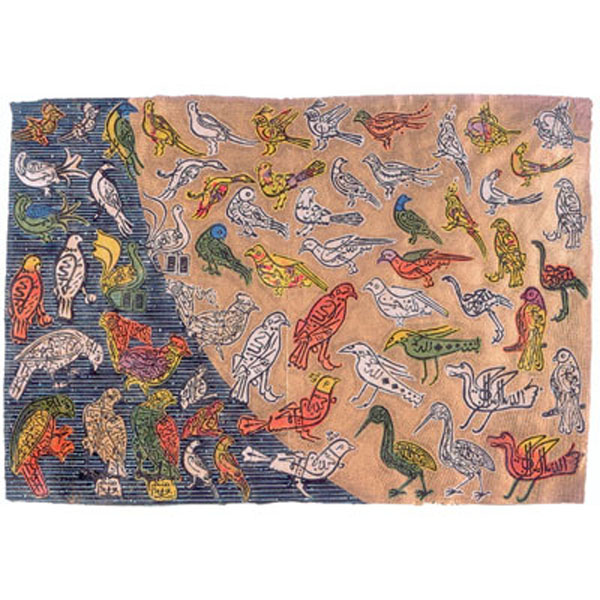

The motivation to twist text into images has as much to do with human curiosity and ingenuity as the Islamic prohibition on image-making. The pious pictures are often associated with the Bektashi order whose origins are obscure and history fragmentary. “It’s founder is said to be Haci Bektas-i Veli (1248-1337), thought to be a descendant of the Iman Musa al-Kasim.3 Animals, plants and human figures made of letters existed in branches of Islamic art such as metalwork of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Latel, Indian artists excelled in the construction of these artful tugras. “Many images consist of mirror-image halves, a symbolic reference to the exoteric (zahir) and esoteric (batin) aspects of being.”4

Day specifically chose to work with these images by collecting thirty examples from a wide variety of sources and re-cutting them onto wood printing blocks and printing them by hand using relief printmaking which is inevitably concerned with mirror-images and symmetry. Another link that determined the use of monoprinting – where the blocks are used by hand and not in a press – was anaphora; this is a literary device popular with Attar, where words or phrases are repeated and strung together like pearls:

“Love’s built on readiness to share love’s shame

Such self-regarding love usurps love’s name.” 5

Day sees the repeated printing of the bird-image blocks, which are themselves made up of text, as a visual equivalent. In addition to the block printing which is multiplied by reversing the image through printing on to very thin Nepalese tissue paper, the mostly Indian paper grounds are painted, stained, inscribed, sprinkled with multi-coloured mica, gilded and burnished, depending on the part of the poem chosen to illustrate. Day has no hesitation in labeling his series of unique prints as ‘illustrations of’, which is anathema to most fine artists. His idea of interpretation is to accept the grandeur and seminal quality of work as given force and to rework it, adding a gloss or nuance that reflects the time ond context of its rebirth. These working methods are standard practice in theatre, music and architecture. His cross cultural approach has enabled a modern audience to reappreciate the universality and relevance of ‘Attar’s famous poem.

European parallels to Attar such as The Owl and the Nightingale and Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls immediately suggest themselves. Dante’s Divine Comedy shares the same basic technique as Attar, a structure that leads from the secular to the Divine.6 As a Christian saint has said, ” All mystics speak the same language, for they come from the same country”7

Rose Issa London 2002

Notes

1. See the introduction to Attar’s The Conference of the Birds, (Penguin classic edition, trans. by Dickdavis and Afkhan Darbandi, London 1984).

2. The Triumphal Sun (East-West publications, London and the Hague, 1980).

3. Frederic De Jong, Pictorial Art of the Bektashi Order. The Dervish Lodge (Univ. of California Press, Berkley, 1992, p128)

4. De Jong, op cit.

5. Attar, op cit. p. 70

6. Attar, op cit. p.20

7. P.W.Avery, introduction to The Speech of the Birds (Islamic Texts Soc. Cambridge 1998)

The Conference of the Birds

Illustrated verses of the poem.

1. The world’s birds gathered for their conference

And said: ‘Our constitution makes no sense.

All nations in the world require a king;

How is it we alone have no such thing?

2. ‘Before we reach our goal,’ the hoopoe said,

‘The journey’s seven valleys lie ahead;

How far this is the world has never leamed,

For no one who has gone there has returned.

3. Whoever can evade the Self transends

This world and as a lover he ascends.

Set free your soul, impatient of delay,

Step out along our sovereign’s way.

4. It was in China late one moonless night,

The Simorgh first appeared to mortal sight

He let a feather float down through the air,

And rumours of its fame spread everywhere.

5. But if you are a lover, blush with shame;

Sleep is unworthy of the lover’s name!

He watches with the wind throughout the day;

He sees the moon rise up and fade away.

6 The fleece for him was silk and rare brocade;

With what else should a lover be arrayed’?

I too have known love scent the passing air

What finer garment could I wear?

7. If thousands were to die here, they would be

One drop of dew absorbed w ithin the sea;

A hundred thousand fools would be as one

Brief atom’s shadow in the blazing sun.

8. “The lovely forms and colours are undone,

And what seemed many things is only one.

All things are one-there isn’t any two’;

It isn’t me who speaks; it isn’t you.’

9. And silently their Lord replies:

‘I am a mirror set before your eyes,

And all who come before my splendour see

Themselves, their own unique reality.

10. Study for No. 11.

11. They see the Simorgh – at themselves they stare,

And see a second Simorgh standing there;

They look at both and see the two are one,

That this is that, that this, the goal is won.

Translated by Alkhann Darbandi & Dick Davis

Published by Penguin Classics London 1984

This exhibition has been supported by The Bath School of Art and Design