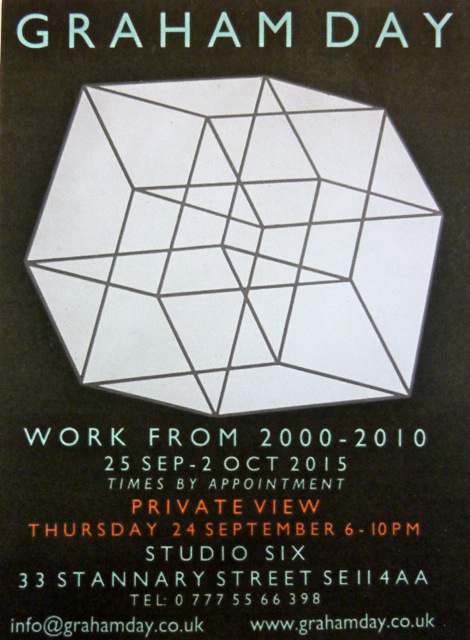

Selected Works from 2000 – 2010

Graham Day: Selected Works from 2000-2010

Studio Six Gallery London: 25th Sept – 2nd Oct 2015

R E A C H I N G O U T

This is the 4th in a sequence of retrospective exhibitions that began in 1970, each covering a decade.

For me the 2000’s began with a solo exhibition at the Forge gallery in Wiltshire showing a compilation of my pieces involving circles entitled Around. The circle with its centre is such a mysterious, fascinating shape, apart from its symbolic value its extreme formal simplicity, its completeness is captivating, it doesn’t lead anywhere or need anything, it is possibly the universal primal archetypal image.

In Spring 2001 at the Art Deco Public Library in downtown Los Angeles Sid Berger organised a large solo exhibition of my work entitled Marbled Mastery. This was an overview of a hundred pieces from my extensive research and experimentation into the art and craft of integral paper marbling, each work being defined by several patterns being combined through stencilling (not collage), to make up the image. The library estimated that 750,000 people viewed the show which brought to an end my fascination with the alchemical world of paper marbling.

I had been invited by the British Council to exhibit my work in Iran. Thinking about Persia and looking at its aesthetic I sensed the visual art connections and influences, which were Chinese from the East and Greek from the West. I was also impressed by the their love of poetry that ran through all strata of society. I decided to make 3 text-based works each saying the same thing in Greek, Persian and Chinese, three different scripts that had distinct, individual forms. I chose a universal message: “If you wish to be loved, love” attributed to Seneca the Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman and dramatist, who died by being forced to drink poison by Nero. The Greek I had carved into a block of marble, the Persian as a mosaic of turquoise tiles and the Chinese cut into two hanging planks of wood. The show was planned for late September but as I was packing it up 9/11 happened and in the following chaos the show was cancelled. The three pieces, bereft of context were mothballed and hung around the studio until it dawned on me a few years later to fill in the gaps between the countries.

This allowed me to address my interest in the pathology of collecting art. I had always justified the pleasure of the addictive nature of acquisition by reference to the useful knowledge acquired by the research involved and the appreciation of the various skills employed by the artists and craftspeople. My fascination of the work of other cultures, mostly Asian items such as Indian miniature paintings, Japanese woodblock prints and Islamic calligraphy coupled with my abiding interest in ‘Pataphysics which is popularly described as ‘the science of imaginary solutions’ generated the additional pieces in the Seneca series where I made examples ‘that should have existed’ thus giving form to a concept. Now this all sounds like the classic excuse of the forger except that my pieces were all documented, signed and dated by me. The viewer has to willingly agree to mentally juggle the appearance of the work with the knowledge that it is not what it looks like. With forgery there is an ‘intent to deceive’, the maker doesn’t want the viewer to question the authenticity of the object whereas I tell the viewer that I made it and it is presented in the context of the overall artwork where many different pieces all say the same thing, i.e. a collection, where the collector attempts to represent a comprehensive overview of the subject. With my work there is an ‘intent to perceive’, the maker wants the viewer to question the authenticity of the concept. Making these other language pieces occupied me on and off until the end of the decade when they were exhibited at the Rose Issa Gallery in London.

I had been making paintings illustrating stanzas from the Persian 12th century epic tale The Conference of the Birds, entitled in Farsi the Matiq at Tar and translated into English by Dick Davis and Afkham Darbandi. It is a search for enlightenment where birds represent basic human types. To illustrate this famous mathnavi I had collected 30 examples of bird shaped zoomorphic calligraphy. I cut the text into blocks and printed them down like large rubber stamps. Rose Issa curated a selection of these, each with the accompanying part of the poem alongside and organised a travelling exhibition that went first to the Museum of Modern Art in Tehran in 2001 where the audience was familiar with the story. Later they travelled to the Galerie Janine Rubeiz in Beirut, returning to the UK at the Mary Ogilvie Gallery in Oxford and finally in 2002 as part of an international event entitled Simorgh to London’s October Gallery, a fitting venue as it had a strong tradition of showing modern art from different cultures.

In 2003 I met Alda Capparelli and began a fruitful collaboration with her gallery in Kensington. The first show was entitled Naïve Science that pulled together a disparate group of my recent pieces. The title referred to naïve art where an untrained hand might unconsciously create interesting work, I applied the idea to science, in which I had no training.

Next with Alda in 2004 we mounted the show of my work Philosophical Furniture. This consisted of flat painted boards depicting the five Platonic forms mounted on metal stands like display models for use in a lecture on mathematics. These five irreducible forms have been understandably influential, there are Neolithic granite examples; Andreas Speiser has advocated the view that understanding the construction of the five regular solids was the chief goal of the deductive system of the ancient Greeks and canonised in Euclid’s famous work The Elements. Beyond Europe, the Hindu tradition associates the twenty- faced Icosahedron with Brahma, the supreme Creator himself, and as such the shape is considered a map of the universe. Johannes Kepler mistakenly though that he had penetrated the secrets of the Creator and discovered the underlying organization of the solar system within their spatial interrelationships. I was interested in representing them in 2 dimensions, playing with tricking the brain into reading them as convincingly 3 dimensional. That sparrows came to peck at the grapes realistically painted by Zeuxis led Goethe to dismiss all talk about deceiving the eye as ‘sparrow aesthetics’ yet “…many illusions of perception are more than mere errors: they may be experiences in their own right. They can illuminate reality, it is this power of illusion to illuminate which the artist somehow commands” (Gregory and Gombrich).

Thus over the millennia the five shapes, unique objects of fascination, have been the inspiration and support of numerous minds and hands, Today they no longer command the respect of scientists who now study dynamic forms and the five forms have been returned to the cabinet of curiosities. I added to this disappointment by making mine capable of being used as tables, useful supports but ultimately mundane.

Later in 2004 at Studio Capparelli we exhibited Plato’s Shadow, a continuation of working with the Platonic forms and illusion. I made large flat versions of the shapes cut from fibreboard and painted with metal paint and splashed with acid and mounted on bases of stacked-up marble blocks, these were accurate transcriptions of the German goldsmith Jost Amman’s 17th century engravings of the 5 Platonic Solids. I mounted them with adjustable hinges that allowed them to cast shadows on the wall to illustrate Plato’s four stages of awareness outlined in his famous dialogue the Republic.

The stages were:

eikasia – illusion, shadows, reflections, tricks of the light.

pistis – belief; objects or ideas that might or might not be true, an element of trust is involved. These first two stages were considered to be doxa – opinion.

dianoia – reason, rationalization, and measurement of things from the preceding categories.

episteme – pure thought, appreciation and understanding of why and how things really are.

These last two categories were considered noesis – knowledge.

Accompanying the models I made a set of paper gilded transcriptions of the same images.

In 2006 I exhibited in the US a group of paintings under the title The Game of Life. These derived their form from board games. There were no rules, they were not for playing on, the imagery displayed an arena, where action unfolds aimed at reaching a conclusion. Like board games I hinged them in half and in addition added tape ties to the boards so that they could hang up and be displayed when desired and stored away like oriental scrolls when not.

In addition there are other individual works displayed that were not part of large themes

Graham Day 2015

STUDIO SIX LONDON